How COVID-19 Has Magnified Pre-existing Inequalities in the US

By Ellie Hu

The distribution of wealth and resources in the United States has been extremely unequal in recent decades, as the share of national wealth owned by the top 1 percent has increased from less than 25 percent in the late 1970s to around 45 percent more recently. In 2022, the top 1 percent income earners in the US took home 20 percent of the total income, while the bottom 50 percent received just 10 percent. Based on the measure of the Gini coefficient for income, the US has the highest inequality among all developed countries and more than a quarter of the world’s billionaires live in the United States.

Though these disparities existed well before the COVID-19 pandemic, the global health crisis has undoubtedly exacerbated the socio-economic inequality in the US and triggered new concerns over rising inequality.

The Economics in Context Initiative’s (ECI) teaching module on Social and Economic Inequality examines recent trends in inequality and presents rich empirical data and real-world examples to understand the causes and consequences of inequality. The module explores the role of globalization, technological change, the changing nature of work, as well as various tax policies and welfare programs in the rise in inequality. The module also considers policy suggestions to address inequality, discussing the ethical and political debates that are often driven by strongly held values.

Incorporating the latest data from ECI’s teaching module and other sources, this blog explores two major impacts of COVID-19 on US inequality—the uneven access to healthcare resources focusing on differences in vaccination rates, and the gap in labor market outcomes. Both factors can cause serious setbacks to long-term social-economic development.

Uneven access to healthcare

COVID-19 has disrupted the US healthcare system with increased demand for medical care, testing and vaccination. During periods when infections surged, the ability of the healthcare sector to provide adequate medical care was seriously constrained. A National Pulse Survey collected by the US Department of Health and Human Services found that the biggest challenges for hospitals during March-April 2020 included severe shortage of testing materials, hospital beds and personal protective equipment (PPE) supplies, along with staffing shortages. As the Omicron variant pushed cases to a new record in late 2021, nearly a quarter of US hospitals reported serious staffing shortages, either due to illness or people quitting because of exhaustion.

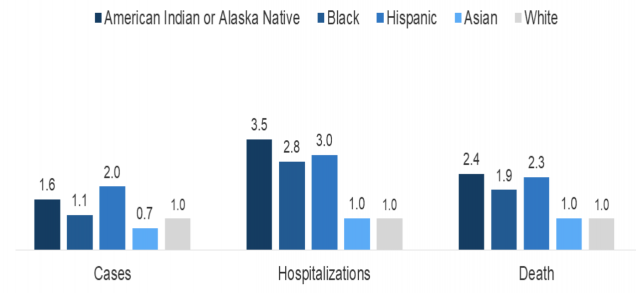

The pandemic has had a disproportionate impact across different socio-economic groups in the US. As shown in Figure 1 below, the infection and mortality rates for American Indians or Alaska Natives, Blacks and Hispanics are much higher than the rates for Asians or white people. The gap in hospitalization rates is also stark, where American Indian and Alaska Native, Black and Hispanic people experienced three times more hospitalization than Asians and white people.

Figure 1: Risk Infection, Hospitalization and Death due to COVID-19, by Race, 2021

Note: Numbers are ratios of age-adjusted rates standardized to the 2019 US intercensal population estimate.

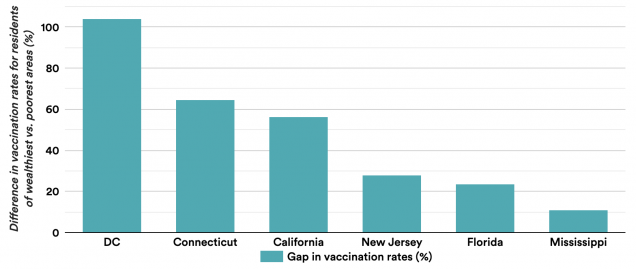

Vaccines are widely available in the US, but a vaccination gap between the richest and poorest communities is evident—vaccination rates for the wealthiest 10 percent of countries are significantly higher in California, Florida, New Jersey and Mississippi. One study argues that people of color have particular concerns over the safety and effectiveness of vaccines. The hesitation often delays their decision to get vaccinated. There is also some evidence that access to hospitals is limited in poor, rural areas within US states. State policies, such as setting up vaccination hubs closer to vulnerable communities and sharing consistent health information could help narrow the gap.

Figure 2: States where the Rich are Vaccinated at Higher Rates

Inequality in the labor market

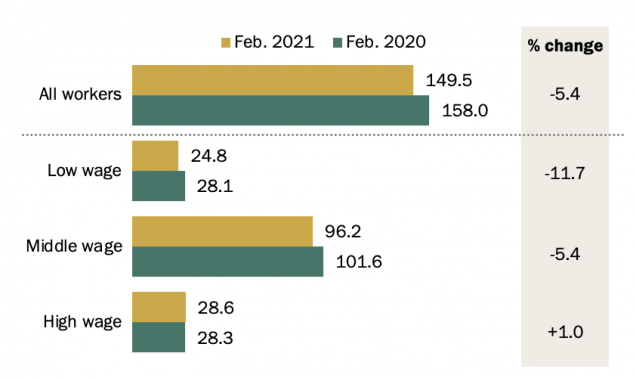

The pandemic has disproportionately increased unemployment rates and worsened working conditions for low-income workers and racial minority groups in the US. While employment for high-wage workers remained roughly unchanged at about 1 percent, low-income workers experienced a much larger decline in employment of about 11.7 percent between February 2020 and February 2021. During the same period, the decline in employment for high-wage workers was only 1 percent. As service sectors were hit heavily by the pandemic, low-income workers in industries like hospitality suffered the worst economic pain.

Figure 3: Decline in Employment (in millions) for Different Income Groups, February 2020–2021

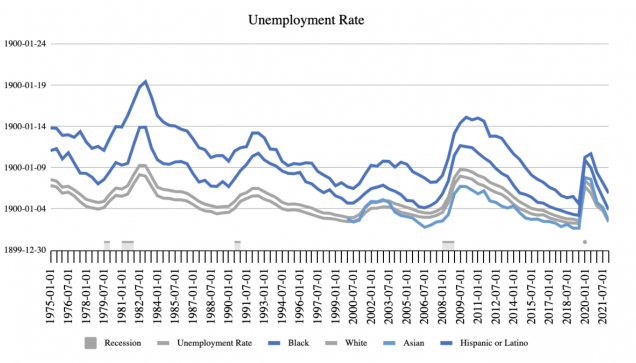

Additionally, there is also a large gap in unemployment rates by race and ethnicity. The US Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that from 1975 to 2022, the unemployment rate for Black and Hispanic people has been consistently higher than for white and Asian people. In January 2022, the unemployment rate for white people was 3.4 percent compared to the 6.9 percent unemployment rate for African Americans. Even though the gap in employment has narrowed in recent years, racial disparity persists—during the COVID-19 peak period, the unemployment rate for Black women was 3.1 percent higher than that for white women, but still 3.2 percent lower than that for Hispanic women.

Figure 4: Unemployment by Race and Ethnicity, 1975–2022

Beyond income, the data also reveals concerns about working conditions. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDD) alerts that “racial and ethnic minority groups are disproportionately represented in essential work settings such as healthcare facilities, farms, factories, warehouses, food processing, accommodation and food services, retail services, grocery stores and public transportation”. These working settings indicate a closer contact with the public, less chance of working at home, less paid sick days benefits and greater chances of exposure to COVID-19-related disease.

Responding to inequality

ECI’s module Social and Economic Inequality offers three broad policy approaches: tax and transfer policies; wage policies; and public spending and regulatory policies.

A more progressive tax system will help balance the after-tax income inequality in various countries by shifting more of the overall tax burden to high-income households. Comparing pre-tax and post-tax income of the US with countries like Finland and Sweden shows that while inequality based on pre-tax income is similar, overall inequality is lower in Scandinavian countries due to more progressive tax and larger welfare systems. Economist James Boyce suggests the fiscal capacities of countries can be strengthened by encouraging tariffs on luxury imports and ending ubiquitous tax exemptions granted to the international community. The resultant generated revenue can then be invested in public goods and services, like healthcare.

Another solution would be to raise the minimum wage. This policy is most effective when it is precisely targeted to the low-income adult earners, rather than younger, non-poor workers. While there is some concern over the increase in unemployment with increased wages, empirical evidence shows mixed results leading to no conclusive relation between unemployment and wages.

Finally, welfare programs to support the most vulnerable populations through food stamps and welfare benefits, as well as large public programs to provide access to health care and education, are central to reducing inequality. Additionally, initiatives such as guaranteed basic income and government job guarantees, or higher investment skills training could help build long-term infrastructure for development.

The COVID-19 pandemic presents unprecedented challenges to social and economic stability in the US and around the world. But with these challenges come opportunities to reduce economic and health disparities for a brighter and more inclusive future for all.

*

Never miss an update: Sign up to receive ECI’s newsletter.