Signs of Hope? Reflections on the Decades-Long Underestimation of Growth in Renewable Energy

By Stacey Yuen, with contributions by Dr. Brian Roach

Two of the world’s most renowned energy agencies, the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) and the International Energy Agency (IEA), have been consistently inaccurate at forecasting the growth of renewable energy. Their underestimations gives us some optimism for the global energy transition that is urgently required to avert the worst impacts of climate change, argued ECI Senior Research Fellow Dr. Brian Roach in a recent presentation at the 2021 International Society for Ecological Economics conference.

The economics of renewable energy is changing rapidly. In 2018, common consensus reflected in the Economics in Context Initiative’s (ECI) Environmental and Natural Resource Economics textbook was that fossil fuels could lose their price advantage over renewables. But, according to Roach, in a surprise twist that most economists failed to predict, a significant share of newly added renewables are now already more affordable than fossil fuels.

As Roach noted, the EIA and IEA’s track record of severely underestimating the cost reduction and adoption of renewable energy suggests the global community is more on track to reach net-zero emissions by 2050 than current projected numbers indicate.

Under the EIA’s most recent reference case projection – a conservative estimate based on historical trends in energy production, delivery and consumption technologies, and without major policy changes – the world will still obtain 68 percent of its energy from fossil fuels by 2050. Meanwhile the IEA, a Paris-based international agency, estimates fossil fuels will still account for 56 percent of the world’s primary energy demand by 2040 under a “sustainable development” scenario, where sustainable energy objectives including the Paris Agreement, energy access and air quality goals are fully achieved.

However, both agencies’ estimations have historically missed the mark.

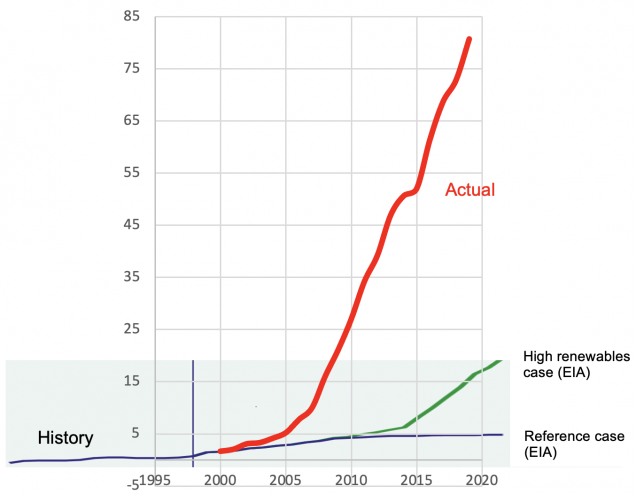

In 2020, actual wind energy generating capacity dwarfed the projections made by the EIA in 2000 for its more ambitious “high renewables” case by four times, and by 16 times for the EIA’s reference case (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1. EIA US Wind Projections vs. Actual (in GW)

Likewise, in 2019, the European Union obtained 34 percent of its electricity from renewable sources. This figure significantly outweighed projections of 10 percent and 5.2 percent for the more ambitious case and the reference case, respectively, that the IEA set in 2000.

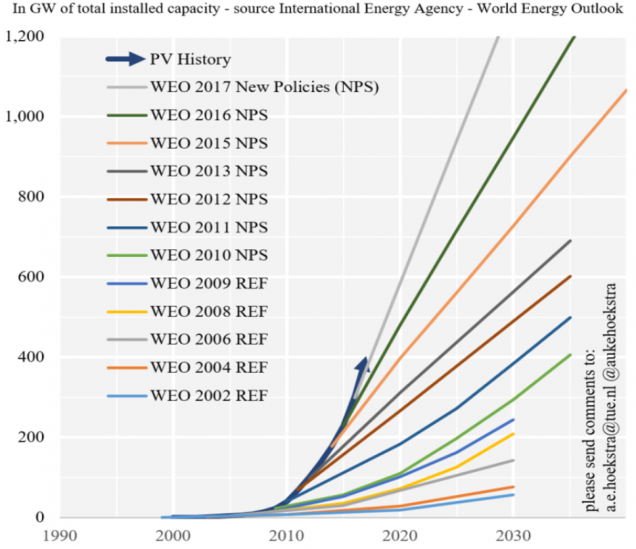

Both agencies’ revisions of their projections over the years also underscore the fact that their methodologies have had to catch up with the actual growth rate of renewable energy sources globally. Between 2017 and 2019, the EIA increased its 2040 renewable forecast by 60 percent. Likewise, the IEA has revised its World Energy Outlook predictions of renewable energy upward multiple times since 2002, as shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2. Cumulative Photovoltaic Capacity: Historic Data vs. IEA WEO Predictions

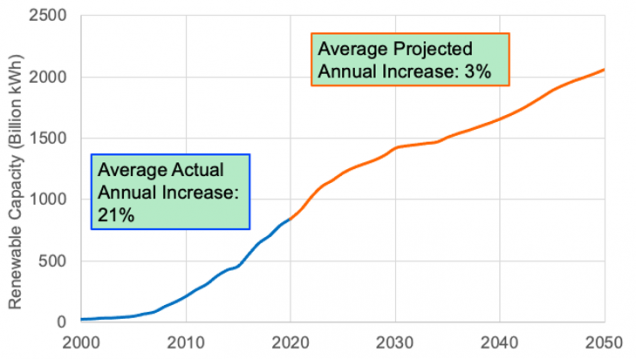

Additionally, Roach argued that the latest renewable energy projections from both the EIA and IEA still significantly lag actual historical trends. The EIA predicts an average projected annual increase in renewable generating capacity in the US of 3 percent between 2020 and 2050; however, the average actual annual increase from 2000 to 2020 has been much higher at 21 percent, as shown in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3. Current EIA US Renewable Projection

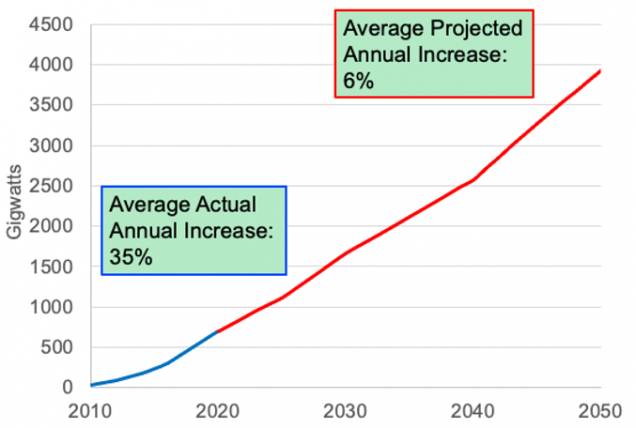

Similarly, the IEA predicts that global solar generating capacity will increase at an average annual rate of 6 percent from 2020 to 2050, but the actual average annual increase between 2010 and 2020 has been 35 percent, as shown in Figure 4 below.

Figure 4. Current EIA Global Solar Projection

According to Roach, the EIA and IEA’s estimations are not improving with time. He suggests three explanations for the consistent under-estimates. One is that the EIA and IEA projections incorporate analyses from energy experts in the private sector, which may have a financial incentive to maintain the dominance of fossil fuels. However, it’s worth noting that forecasts produced by the British multinational oil company BP have generally been more accurate than those of the EIA and IEA. Most recently, BP projects that renewables may make up 45 percent or more of global primary energy consumption in 2050, if supported by significant policy changes including a sharp increase in carbon prices.

A second possible explanation is that the EIA and IEA have developed their forecasting methodology over several decades, and for most of this period energy shares changed little and there were not dramatic technological advancements in renewable energy. Thus, they have not adapted their analyses to the rapidly evolving environment in current energy markets, according to a paper published by the EIA in 2016 addressing some of the critiques on its forecast of the growth of renewable energy.

Finally, baseline projections are developed using existing policies, while actual policies in the US and elsewhere have increasingly promoted renewable energy.

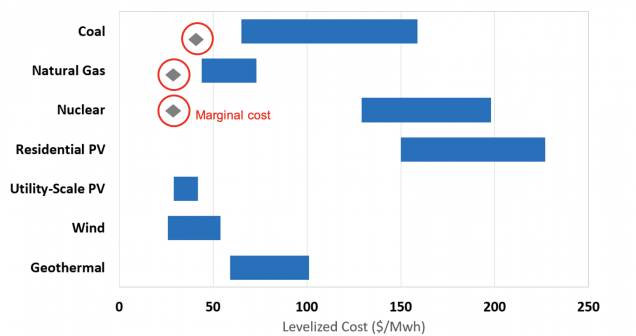

Although government subsidies have helped, the affordability of wind and solar energy globally is driven primarily by pure economics, Roach said. Notably, new wind and solar energy is becoming competitive with the marginal cost of fossil fuel energy, as shown in Figure 5 below. In other words, the cost of installing new wind and solar energy is getting more affordable than running existing fossil fuel plants.

Figure 5. Current Levelized Costs of Energy Comparison

The demand for fossil fuels looks set to peak in the near future. In the meantime, the levelized costs of renewable energy continue to fall rapidly, with the possibility of declining to $0.01-0.05/kWh by 2050, according to a 2019 study by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Given these factors, Roach argues for tempered optimism, if combined with continued action, for a future of sustainable energy practices globally.

With the ever-changing pace of development in renewable energy, the ECI remains committed to continually updating its teaching materials on energy economics to include the latest data and trends. Educators seeking to incorporate these materials into their lesson plans should explore our free-to-use teaching module on Energy Economics and Policy, which was updated in 2021, and keep a lookout for the fifth edition of the Environmental and Natural Resource Economics textbook, due to be released end-2021.

*

Never miss an update: Sign up to receive ECI’s newsletter.